Former mayor of Fort Wayne, former president of the Brady Foundation, and current director of the Civic Leaders Center at IU, Paul Helmke, was interviewed on The Colbert Report in 2008 in a segment of Colbert’s “Better Know a Lobby” series. Helmke acted as a representative of the gun control lobby in the segment, and he always talks about his appearance fondly.

Professor Helmke was my professor for both Legal History and Law and Public Affairs, and when he discusses the 2nd Amendment, he likes to play this segment for the class.

Unfortunately, however, full episodes of The Colbert Report are no longer legitimately available anywhere on the internet. In class, Helmke has had to resort to an old recording from COVID of a student watching the clip.

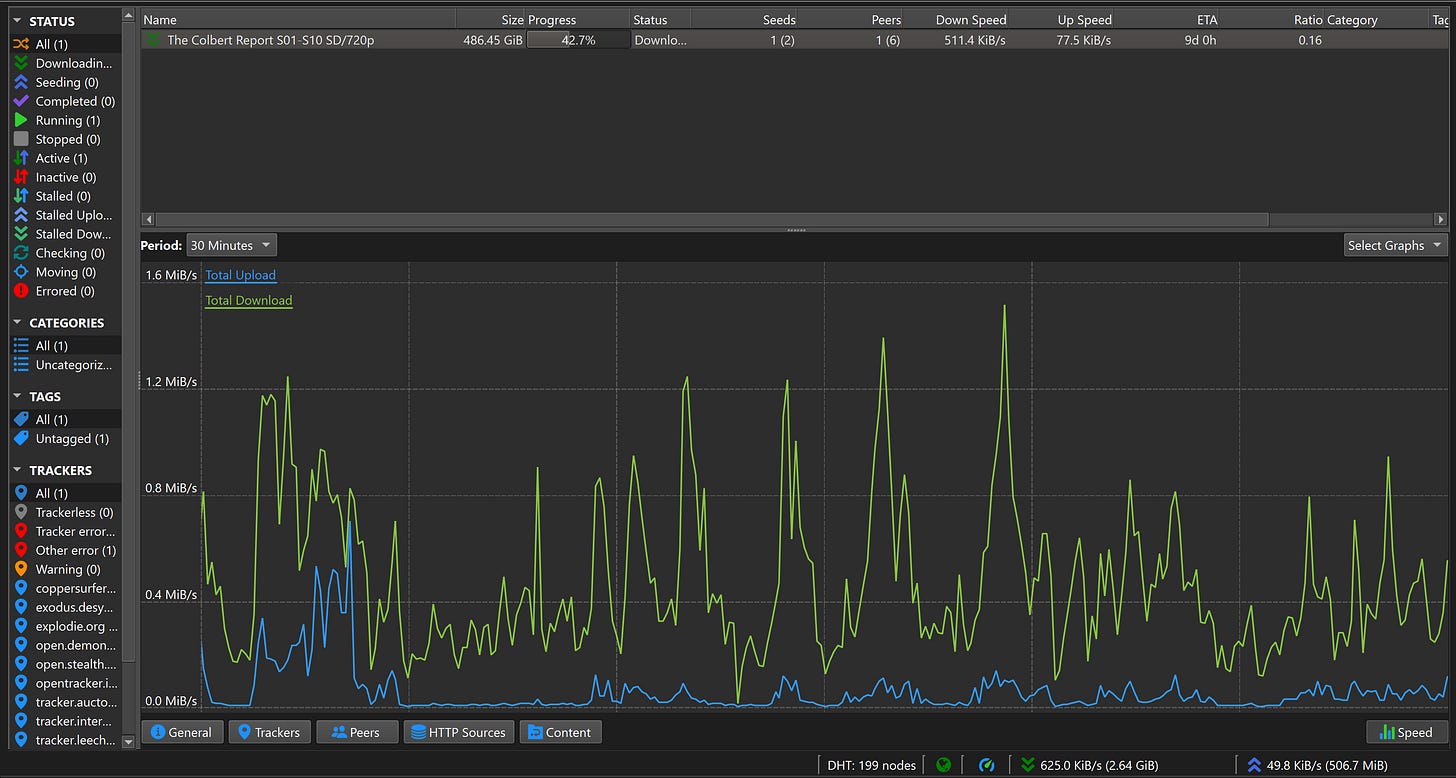

Notice how I specified “legitimately available,” because there is still one way to get every episode of The Colbert Report, and that’s piracy.

This isn’t an isolated case. Vast swaths of media history—television, film, music, video games, even websites—have simply disappeared. According to the Library of Congress, over 70% of American silent films are considered completely lost, and similar rates of disappearance afflict early TV broadcasts and niche internet communities. Corporate consolidation, copyright disputes, and platform shutdowns mean that entire cultural moments vanish overnight.

The only reason we can still access so much “lost” media is because people—often anonymous, sometimes working in outright defiance of the law—took the time to rip, copy, seed, and share it. The Internet Archive has rescued everything from defunct websites to endangered books, but it constantly faces lawsuits from publishers. The Lost Media Wiki thrives as a community hub for people scouring VHS tapes, old hard drives, or forgotten regional broadcasts to preserve fragments of the cultural record. And yet, these projects exist in a legal and moral gray area, because they are sometimes indistinguishable from piracy.

That leaves us with a dilemma: piracy may be illegal, but for much of our cultural history, it is the only reason we still have it. When Viacom or Paramount decide that The Colbert Report no longer fits into their streaming strategy, do they have the moral authority to let it disappear? When a publisher sues the Internet Archive for lending scanned books during the pandemic, are they protecting their rights—or destroying public access to knowledge?

Our archival practices, then, are less a technical question than an ethical one. Who gets to decide what survives, and who bears responsibility for safeguarding our collective memory? Right now, much of that burden falls not on institutions, but on scattered communities of “pirates,” preservationists, and digital hoarders. Without them, Helmke’s class wouldn’t be able to watch his appearance. Without them, we would already have lost far more than we know.

So maybe the moral panic around piracy has always been misplaced. The real threat isn’t the illegal torrent—it’s the sanctioned erasure of culture. We should reexamine not only how we archive, but also how we judge those who keep the record alive. Because when we lose media, we lose the stories that made us who we are—and right now, it seems that only the pirates care enough to keep them.